Unburying My Father- Zander Masser

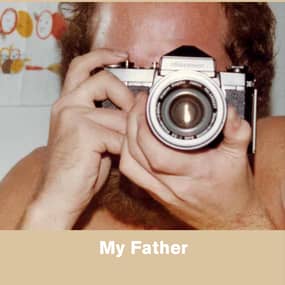

Zander Masser is an occupational therapist, husband, father, musician, and author of the narrative photography book Unburying My Father. Zander's father, Randy, contracted HIV from using contaminated blood products to treat his bleeding disorder and died in 2000 from AIDS-related illnesses. Twenty years later, Zander unburied ten thousand slides from Randy's career as a professional photographer, which prompted him to dig deeper into his father's life. What started as a photography project evolved into a transformative exploration of living with, and healing from, grief. The book, Unburying My Father, was funded by a successful kickstarter campaign. Since then, Zander has delivered talks and workshops around the US and Canada and has created several photography exhibits featuring his father's work.

You can find Zander at:

www.randymasserphoto.com

Thanks for your support. Stay tuned for more exciting stuff next year.

Check out my Substack https://grief2growth.substack.com

You can send me a text by clicking the link at the top of the show notes. Use fanmail to:

1.) Ask questions.

2.) Suggest future guests/topics.

3.) Provide feedback

Can't wait to hear from you!

I've been studying Near Death Experiences for many years now. I am 100% convinced they are real. In this short, free ebook, I not only explain why I believe NDEs are real, I share some of the universal secrets brought back by people who have had them.

https://www.grief2growth.com/ndelessons

🧑🏿🤝🧑🏻 Join Facebook Group- Get Support and Education

👛 Subscribe to Grief 2 Growth Premium (bonus episodes)

📰 Get A Free Gift

📅 Book A Complimentary Discovery Call

📈 Leave A Review

Thanks so much for your support

Brian Smith 0:00

Close your eyes and imagine

Zander Masser 3:01

You know, it's, it's like, if you think about a coffee table book, when you flip through, and there's, you know, professional photos on nice paper.

I thought, well, I should tell his story and then realize, Wow, I don't, I don't actually know that much about my dad at all. Even though we had an incredibly close relationship, I was 14 when he died. And I had, you know, 14 amazing years with him. But I was a child. And we didn't speak as adults, we didn't really have adult conversations. And so as an adult, you know, still to this day thinking about my dad every day, it was like, I can't believe I'm, you know, in my 30s. And I actually don't know that much about my father. And so

Brian Smith 0:03

what are the things in life that causes the greatest pain, the things that bring us grief, or challenges, challenges designed to help us grow to ultimately become what we were always meant to be. We feel like we've been buried. But what if, like a seed we've been planted and having been planted would grow to become a mighty tree. Now, open your eyes. Open your eyes to this way of viewing life. Come with me as we explore your true, infinite, eternal nature. This is grief to growth. And I am your host, Brian Smith.

Announcer 0:47

Hi there. Before we start, Brian would like to share a couple of things with you. First, did you know that Brian is a life coach, a grief guide and a mental fitness trainer? Brian would love to help you with whatever life issues are challenging you. Brian has years of experience as well as training. You can contact Brian at WWW dot grief to growth.com to learn more. Brian is the author of the best selling book grief to growth planted not buried, which you can get on Amazon or Brian's website. This is a great book if you're in grief or to give to someone you know who is dealing with grief. Lastly, Brian creates free and paid resources for your growth. Go to www dot grief to growth.com/gifts www.gr IE F to growth.com to sign up for his newsletter. Choose a gift just for signing up and keep up with what Brian is offering. And now here's today's episode. Please enjoy

Brian Smith 1:50

Hey everybody, this is Brian back with another another episode of grooves to grow. This is I've got with me today Xander master. He's an occupational therapist who's a husband a father. He's a musician and he's the author of the narrative photography book and bearing my father. Zander's father Randy contracted HIV from using contaminated blood products to treat his bleeding disorder. And he died in 2000 from AIDS related illnesses. 20 years later Xander and buried 10,000 slides from Randy's date for Mandy's career as a professional photographer, which prompted him to dig deeper into his father's life. And what started as a photography project evolved into a transformative exploration of living with and healing from grief. The book is called unburying my father it was funded by a successful Kickstarter campaign. Since then Xander has delivered talks and workshops around the US and Canada and create several photography exhibits featuring his father's work. So I'm really excited to have with me today Xander masters. Welcome Xander.

Zander Masser 2:47

Thanks, thanks so much for having me.

Brian Smith 2:49

So first of all, what is a narrative photography book? What does that mean for people that aren't aware of that?

Zander Masser 2:55

Sure. So practically speaking, it's it is a photography book.

I basically created a list of around 40 or 50 people that I thought I could ask questions to about my dad, as a way to get to know him, but really, as a way to tell his story, in order to create this book, with a more maybe wide appeal. And I think with artists in general, it's, it's helpful to know their background, because it, it, it gives insight into, you know, what their art is why they made it that way. And, you know, there's, it provides some substance, I think, to the art. And so, anyway, I just, you know, I received this incredible response where like, you know, every day for several months, these stories would flood my inbox about my dad, and, you know, I would just sit there and cry and laugh. And you know, the thing that was so helpful about this, and why I use that term narrative. So purposefully is that I asked people to share stories with me, I didn't want them to say, to like, describe my dad, like, oh, he was small, or he was funny, or whatever. I wanted to hear the stories that back that up. And, you know, as you probably know, there's a lot of power in storytelling. And we can learn a lot by telling stories and hearing stories. And, man, I received dozens and dozens and dozens, you know, about 80 pages worth of stories. And basically, what I did was I pieced those stories together, which also obviously, include my own stories, and those of my mother and my brother, to create the arc of my father's life. And so the book takes you through, you know, from the beginning of his, you know, the first week of his life until the day he died. And after. And so that's, that's how the book goes. And yeah, so that's why I use that term narrative photography.

Brian Smith 7:38

Yeah, that's, that's a really interesting process that you went through. So you're you were a child, when your father when your father died. So what did you learn about your father going through this process? I'm sure you had a whole different perspective.

Zander Masser 7:52

Yeah, I learned a lot. You know, the first thing I think that happened was, instead of learning more confirming some of my memories about him, because I remember him being this very funny, very lovable character. And from the stories I received, that that was just confirming for me that people he was almost like a universally loved person in a way that people just felt comfortable and connected to him very easily. Whether it be his best friend from college or someone, a nurse, he, you know, that was on his care team that saw him every three months, it could be anyone and they just, there's that similar sentiment about him. So that was confirming the things that I learned about him, that really were revelatory for me were was actually actually came from kind of missing information, which was that he didn't talk to anyone about his illnesses, his fear of death, his anger, you know, my dad was born with a bleeding disorder, which severely limited his his life in many ways. He had a physical disability because of it. And you know, he couldn't do a lot of things he wanted to do. And then using the medication to treat that disorder, he contracted HIV which led to AIDS and led to his death. And so, you know, you can only imagine how much must have been going on inside of his head and in his brain and in his heart psychologically and emotionally and he kept that to himself. And one of the things my mom shared with me was that it was his wish to maintain positivity and I, you know, I use quotation marks for those who can't see me because what that what that looked like, on a daily basis was total silence around The fact that in our household there was a person with, you know, disease and infectious disease, a terminal illness. And so that was a huge piece that I learned about was that my dad just could not, did not, would not speak to his family or his friends about it. And, you know, I learned subsequently about myself, which was that, you know, that was a learned behavior. And after my dad died, I totally took that on. And, you know, I went through my own trauma of losing my father and living with severe grief for a long time. I didn't talk to anyone, you know, I was put in a room with a therapist after he died and bereavement groups and stuff for a little while. But I wasn't willing, and I wasn't ready to really talk about it. And only in retrospect, and learning about my father, and about my family, and my mom's experience, that I learned that, and there was a total missed opportunity, I think, on my father's part, to speak to us more about what was going on, but he didn't. And so, you know, there's, there's a lot of mixed emotions and mixed feelings about, you know, feeling anger towards him all these years later for that, but at the same time feeling so much compassion and empathy for him and for my mom, because, you know, their situation was just so hard. And you know, I'm a new father now, and I just can't imagine trying to have that conversation with with my kid. I do think it's possible. And I think that there, there are ways it could have been done, and it wasn't. So I'm kind of met with this. This juxtaposition of anger and empathy and compassion and love all mixed up together. And, you know, I'm okay with that. I think that's like, kind of, you know, one of the end results is like, just acknowledging all of that, and being okay with it makes me feel better. And as part of my growth and my healing and my grief.

Brian Smith 12:14

Yeah. Well, you know, you talked about not being ready to talk about it at 14, but a lot of, and there, we do have learned experiences for our parents, of course, but kids also grieve differently, especially I think teenagers do, we don't really know how to handle our emotions at that age. So I'm curious, you, it's, it was 20 years when you uncovered these photos that you find them 20 years later.

Zander Masser 12:39

So I actually found them with my brother 10 years after he died. So about a decade after, at that point, we were my mom was still living in our childhood home. And my brother and I, one day just went down. And we're like, you know, we know dad was a photographer, we grew up with his beautiful photos on our walls, and, you know, family photos, he was really talented, but we were like, he must have left more than that, more than what's just on our walls behind. And we were, you know, without articulating it looking for an opportunity to reconnect with him. But, and, wow, I mean, you know, it was just amongst what someone might imagine, in the rubble of a basement that's been untouched for a long time, is mostly disorganized. But it was all there. And, you know, my brother and I, we just, we would take slides and just hold them up to the light and, and like, wow, we were so amazed by some of the imagery, even just looking at it like that. And so our initial idea was just to like, share his photography, let's just share his work. But we didn't have any money to like, get them digitized. And we didn't have a machine to do it ourselves. And I was, we were both living in other parts of the country. So it just like didn't nothing materialized. Fast forward, literally another 10 years. After, you know, the photos have been boxed up, moved around, our house was sold, my mom moved around a few times. It was in storage units, different basements. And finally a family member of mine knew that I had an interest in doing something with the photos and she gave me an old slide scanner that he or she had sitting around. And so that's actually what prompted me to collect all 10,000 took them home with me with this machine. And, you know, I didn't know what this was going to look like I never done this before. But I just became obsessed doing this and I scanned all 10,000 of them manually myself and created an archive so it's totally organized and it's physical ended. Utah. And that's kind of how this all started. And but you know, at least that's, there was like the initial idea 10 years after he died, and then really things starting to happen 20 years after.

Brian Smith 15:14

So is that when you started interviewing people for the for the book?

Zander Masser 15:17

Yeah. So once I, you know, could see the photos on my computer and go through all the photos, which I did many times. That's kind of what prompted the next that other step I was kind of doing them in conjunction. And one of the amazing things was that, and this is really what I think, gave life or gave wings to this project, which was that, you know, I had seen the photos many times, and I got to know them. And as the stories flooded in, I started to see this connection between my dad's lived experience, as told by people who loved him, and the photos that he decided to beautifully capture with his camera. And so, you know, one that always sticks out to me is this this story that my dad's first cousin told from when they were like, five years old, or something a little kids. And my grandmother, my dad's mom had planned to take my dad and his cousins to the Statue of Liberty. They were living in an apartment in New Jersey. And he's telling the story about how they're playing outside the apartment before they were supposed to leave. And my dad jumped off a bench and hit his knee and his knee blew up like a balloon, which is characteristic of people with hemophilia. And they didn't go that day, and my dad had to go to the hospital to get a blood transfusion. And, you know, as I go through the photos, I found probably a dozen of these incredible photos of the Statue of Liberty have different angles and different colors of the sky. And just they're so beautiful. And and I thought to myself, like, I wonder, I wonder if he was conscious of that memory when he took the photo? Or if not, I wonder if it's still subconsciously playing into his experience of being there, photographing it, even deciding to photograph it at all. And, and so in that way, I started to feel kind of collaborative with my dad. And it also helped me to piece together the book, where some of the stories are kind of matched with photos, you know, that's a kind of literal example, sometimes there's more abstract examples. But that experience was so profound for me. And that's what I kind of referring to earlier about, like, providing back an artist's background as to why they're doing the art they're doing. And this really gave life to his photos. So that that brings the book together.

Brian Smith 17:49

Yeah, I think that's, that's really interesting, because, you know, a very, very long time ago that people have listened to podcast before I tell the story all the time, I took a little mini course is called what you are was where you were when, and I think, to really understand people, we really need to know their backgrounds. And as children, we don't know a lot about our parents, we think of them as these big, perfect beings, you know, for a while, and then we think of them as not so great. But we don't understand what is what those traits came from. So I imagine you learned a lot about your father, and were able maybe to relate to him better after going through this process.

Zander Masser 18:25

Yeah, totally. You nailed it. Because, you know, when I went into this, I totally viewed my father as like, this idealized version of a human that could do no wrong, or, you know, I could never be mad at or, you know, you know, just just not a whole virgin, and after learning about his story, and the story of, you know, tainted or contaminated blood and how it all went down, you know, so many pieces of his life that I didn't know about. And so I have this whole version of him now. And I'm so happy about that, even though maybe there's some parts of it that make me angry or resentful, or, you know, like I was talking about before in terms of his silence, like the fact that I know him as a person and not this, you know, idealized figment of a person has been really helpful for me.

Brian Smith 19:23

So did you learn like where his silence came from? When you were doing the background? Did you find out maybe why he had that trait?

Zander Masser 19:30

I think there's a lot of factors involved. Not not specifically, but I think I know that his parents weren't really open to kind of like being vulnerable and talking about those types of challenges. I think there are probably generational factors. You know, I think my dad's generation didn't grow up in a household where he talked about that. And obviously, you know, there's so much stigma around HIV and AIDS, you know, he he contracted In the early 80s, so it was so much not known about it. And it was pretty typical for someone like my father to not talk about that with Yeah. So, you know, I acknowledge all those things

Brian Smith 20:16

for sure. How was your father when he passed? He was 52. Okay. Okay, so, yeah, so yeah, and the ad is, well, you're right, there was not a lot known about AIDS, and then there was a lot of stigma around it, even when we did find out things about it. So I would imagine that played into, you know, him that we're not going to talk about it either. Definitely. So, you know, as we were talking right, before we start recording, I think it's really interesting to talk to people about different types of grief and different grief processes. So for those the several years between the time your father passed 20 years, and the time that you worked on this project, how are you processing your grief at that time?

Zander Masser 21:00

You mean, along those 20 years?

Brian Smith 21:02

Yeah, along the 20 years?

Zander Masser 21:06

Mostly in silence. You know, when I say silence, I mean, my internal dialogue was very loud. But without really talking to many people about it. You know, I, I spent a long time thinking about how my dad's death impacted my life. You know, as a young adult, I asked myself, you know, the question that I think a lot of young adults ask, which is, you know, why, why am I who I am? Who am I in this world? You know, existential questions, which are important to ask, the answer that kept coming back to me was, while I am who I am, because my dad died, I'm, you know, maybe I feel socially uncomfortable, because, because my dad died, or because I'm grieving, or maybe it's hard for me to stay in one place. Maybe I can't let go of people. You know, there's a lot of traits about me that I tied in to my dad's death. One of the things you know, I'll I'll jump. I'll jump around a little bit here, if that's all right, yeah, sure. One of the things, you know, after the 20 years, and one of the one of the revelatory aspects of this project, was that it allowed me to see that my father's life impacted me so much more than his death. When, and I could only know that by learning about his life and how he lived and how, what kind of person he was. And looking back now, all those years later, it was like, why was life left out for grief work for me, you know, like, there was so much talk about how to deal with death. Where's the life in that? And it just got left out? And, you know, I think that's, I don't know how common that is. But I feel like, it is common because it's we try to learn coping mechanisms or ways to process death. But I think the best way to process death is to focus on life. And I've only kind of learned that fairly recently. But it's never too late to learn that. And, you know, I spent every day and I still do, I think about my dad every day, it's never gone away. So, you know, the idea that people move on or, you know, you got to keep busy and forget about the past, you know, these these tropes that that we all grieving people here is, you know, they're not they're not true, and they're not helpful. You know, I think other ways that I was processing was, you know, using alcohol using drugs. I wasn't in like, any trouble, per se, but, you know, I think I was using too much to a point to maybe numb myself a little bit and have a bit of some classic behavior. I think. So, yeah, you know, it's been it's been a long journey. But it's, you know, I've come to a good place.

Brian Smith 24:17

Yeah. What you said, that was so profound, I just want to echo that back. You know, the thing is, a lot of times we're a group we do focus on on the death and we focus on the bad things, we focus on the illness. So we remember people that way, and we forget about the great years, the great time that we had with them. And this process, I guess, kind of forced you to look at your father's life, as opposed to focusing on the end.

Zander Masser 24:44

Definitely. And and to add on to that, you know, my dad certainly lived with grief while he was alive, you know, he he lives with a lot of loss and his loss was not death, but it was loss of his good capacities, you know, the loss of freedom to do whatever you wanted to do, and, you know, a slow deterioration. Yeah. But he was not ever known as being a sick person, he did not identify as an angry, bitter, Ill individual. He was he identified as an artist, he was known as a person who gave love and light everywhere he went. And so that's kind of an analogous to what we're talking about is that, you know, even in grief, the life needs to be there. And it can it can, it can overpower the grief or at least, you know, give a spin a positive spin to it.

Brian Smith 25:51

Yeah, you're right. And I think, fortunately, we're getting to that, I think, in grief work with people where there's the term that's used now, it's called continuing bonds. And the old days, it'd be like, okay, that person has gone there, you're never going to see them again, your attachment is unhealthy. So let it go and move on. And realize that doesn't that doesn't work? As you said, You were you were a child, when your father passed, and 20 years later, you still think about him every day? And that's, I think it's I think it's healthy. I, you know, I think it's, I think it's fine, as long as we can put their life in perspective that we're not, you know, we're not allowing it to hold us back from our lives and using as inspiration move forward. I think this distribute, you've given your father is just awesome.

Zander Masser 26:37

Well, thanks for saying that. And I love the term continuing bond, because that's exactly what this project has done for me. And it's like, go back to your question about how I was processing for 20 years after it was like, I felt stalled. You know, it was like a stalemate, I just ate in this one quiet place where, you know, I just talked to myself about how shitty it was that my dad died. And now that there's just so much life involved in in how I think about him, and specifically in terms of continuing bond, because I have this project and because I'm, it's not, it's, it's the book, and I'm also presenting it, as a photography exhibit, I'm giving talks, I'm giving workshops, you know, I'm very active with it. My dad and I are currently interdependent on each other. And in order to share his photography, he needs me to tell the story. And I think in order for me to tell the story, I need his photography, because they go hand in hand, and they they make each other more compelling. And so you know, if that's ever an example, if there's ever an example of continuing bond, I think that's a really, really good one.

Brian Smith 27:54

Yeah, I think that's absolutely beautiful. And the thing is, things shitty things happen to all of us in our lives, right? And it's so it's not a matter of if they're going to happen to us. It's when they happen to us and what's going to happen to us, but the real question is, what do we do with it? You know, how do we move on from that, you know, how do we take that and turn it into something that's, that's beneficial to your to ourselves and to everybody else. And that's why when I saw your story, I was so moved by it and said, I really want to have this guy on and talk about this. Because we all have to process grief differently. And I think this is a really unique and interesting way to do it. I interviewed a young man on my program that his father died when he was like 12, or 13. And he started a company where people can come and like, share their legacy while they're living, like record videos to leave to the kids, because he said, I don't want anybody to ever have to go through this again. And you're, and you're showing like, okay, I can even even 20 years after my father's passed, and I could still take this and make something of it.

Zander Masser 29:01

Yeah, totally. And I think, first of all, you know, not everyone's, the person that you're grieving, whoever's listening out there, you know, not everyone's grieving, professional artists, or someone who left behind, you know, 1000s of artifacts from their career. I got, well, I'll say I got lucky in that sense, only because, you know, my dad left behind such an amazing legacy. But everybody leaves behind a legacy no matter what. And what you know, that's a major tenant of the workshop that I give, and it ties into what you're saying about what we do with grief, we need to make meaning out of it. And so the workshop I put together is basically I took my creative process and broke it down into 10 concrete steps, and it's a process for creating Memorial Art. And so, at the end of the workshop, up, the participants have a roadmap for how to memorialize someone they love. And so for me, it turned out to be this book and, you know, many other aspects of my project, but for somebody else, it would be totally something totally different. So the point being that they don't have to create a professional photography book, they could create a dance, they could create a meal they could do, it can be as small or as big as they want. But it's a way to open up the conversation and continue the bond as we're talking about.

Brian Smith 30:32

Yeah, I think that's beautiful. I'm glad I'm so happy you're doing that. And it's interesting that I found that I think, you know, we're not all artists, I know you're, you're an artist and a musician, and you get the book and your father's a photographer. But I think we all have a need to create an on some level. For me, I give speeches, I write I podcast, I do stuff like that. I think we all have that kind of that desire, and is but we have to find out what works for us what what is our outlet for our grief. And I like bringing people with different examples. Because again, no one's going to follow your exact path. But they can be inspired by what you've done and said, what would what would the legacy be for my loved one? What did? What did they leave behind? Or how can I learn more about them? The idea of, I think, is brilliant for you, as a child, when your father passed to say, let me talk to people who knew him when he was dying, and let me get some stories, because the few stories I have with my parents is really helped me to understand them, you know, and helps you to forget, I think, I don't know how you feel about that. Yeah,

Zander Masser 31:33

I definitely agree. And it's, it's interesting to hear stories from other people, because I think they tell the stories that our parents just won't tell us. You know, like, I asked my parents those questions, maybe they wouldn't answer but, or they'd give different answers. So, you know, it also just places them in the world outside of you, you know, my parents existed for a long time without me, and they had this whole life. And, you know, it wasn't always all about me, because when you have a kid, it's all about the kid, you know. So, and also just the simplicity of reaching out, it's a simple concept. Who knew my dad? Okay, I can think of many people off the top of my head, maybe not everyone has a huge social network, but I think we can all think of a few people that knew the person were grieving, at what can I ask them, and leave it open. And the cool thing, too, you know, there's so many layers to this. But when I started to speak to some of these people, it led to these deep conversations with them, not necessarily about my dad, but maybe about their life or about my life, or, you know, what it was like for them to experience my dad's death or someone else, you know, it just turns into something else. And just those interactions alone felt worth it to me, because at the core of this project is like, I'm trying to connect, and I connect a lot of dots. But I want to connect on a deeper level. And I've never been able to do it, just by sitting and talking about it. Because I just I wasn't equipped, or I didn't know how but this project has opened up the door to conversation for me. And that's what I want other people to know, especially if they take my workshop is that the outcome is that if you have a hard time talking about your grief, or your loss, here's a concrete thing. You can go out and make it and then talk about it. As opposed to like, here's what happened to me, or here's how I feel right? Now, here's this really cool thing I made. Here's what it's about, and it opens up the conversation in a, I think, an easier way.

Brian Smith 33:51

Yeah. And I think the process is, I don't put words in your mouth, but maybe as important as the final product. You know, the the process those conversations, and, and getting to know people because we tend to think of people as one dimensional, we look at them from our point of view, if it's if it's a parent, then that's my father. If it's a child, that's, that's my child, if it's you know, we look at people as and their relation to us, but people are multifaceted. And everybody views them a little bit differently. And by talking to multiple people, you can kind of fill that picture out as to who this person really is.

Zander Masser 34:28

Totally, and that's a that's one of the major points in the workshop is, you know, trying to encourage variety in people. You know, I talked to this, this guy who was the former executive director of the Hemophilia Association of New York, and I hadn't owned that my dad had some affiliation with them, but I didn't really know. This guy told me that my dad was an active board member for over 20 years. He was their vice president, that he ran you youth groups for young adults with bleeding disorders, that he counseled young families. And that he advocated. He wrote letters to politicians to, you know, to advocate for people in the bleeding disorder community. I didn't know my dad did all that. And so that just like that well rounded view of a person is, I was so grateful to that guy to that he was willing to speak to me and gave me this whole other perspective of my dad that allowed me to respect my father even more than I are, you know, and

Brian Smith 35:37

that's the thing we don't know we're going to learn is my daughter was 15, when she passed, and she lived with us her entire 15 years. And we homeschooled her. So I saw her every day, and I work from home. So I had such a connection with her. But when she passed, and people came and told me stories, like Shayna did this, or Shayna did that, things that I didn't know because we don't know everything about a person. And those things can be so touching to find out that that the person that we love and respect is like even more than we knew.

Zander Masser 36:06

Yeah. Totally. And it's, it's an it's, anyone can do it, I really believe that I want to empower people to just know that even if it's just one person that you know, knew the person that you lost, it's worth it to just ask a few questions, even if you're not going to make a big project out of it. It's that part of the process. That's really important.

Brian Smith 36:31

Yeah, and I think some people will be intimidated and say, Well, I don't know, I'm not creative. I can't, I can't come up with a project. And again, I encourage you to do it. Anyway, I had a client that she was a life coaching client, and I'm not even sure how we started. But we're just talking and she goes, Why don't really want to do I want to leave a legacy. I think I want to write a book about my life. So we went through a process and it was a few months, every couple of weeks we get on, we get on a zoom call. And she would tell me another little piece of her life. And just watching her mind change. And as she went through things in her life. And as I reflected things back to her, it was a really cool product process. I was like, wow, this is I should offer this as a product, because I think we both were impressed, you know as to how it went. So I would say to people that are that are listening to this that say, you know, I don't know what my projects will be. You don't have to have a project just take notes.

Zander Masser 37:27

Definitely you don't you don't have to. But I like what you said there because it kind of ties into, like you're talking about this person wanting to leave their own legacy. Well, the thing that one of the major turning points in my project was when I decided to share my story. And I didn't I'm not necessarily viewing it as my legacy, but it's part of my legacy. It's my my experience of my dad, and my experience of his death. Because I had all these stories from his friends from his family, you know, I got amazing, the vulnerable stories from my mom and stuff from my brother. And then it was like, now it's time for me. And my initial intention, this project was never to be about me at all. But as soon as I started to share my experience, first of all, just the catharsis of writing it down on paper, or, you know, on a computer document was mind blowing to me, because I shared store and you know, it was in that theme of storytelling narrative. And I was sharing, I was writing stories I had never told anyone, including my wife. And that is, to me, that was like, the hook that really brought this project together. And it started to just be about me, and, and my relationship with my dad. And I was surprised that I was doing it. And I was surprised at the impact that it was having on this on the story as a whole and the project and when I would tell people about it or share it. And, you know, I think for people who are listening and are interested in you know, maybe doing a project about their person. One way to make it easier is to tie yourself in and share your story and your relationship with that person. And one of the things I encourage my workshop participants to do is one of the steps is called you. And it's to write down or share a story that you've never or rarely shared with anyone. It's really powerful and it can have a lasting impact. And so I really have rolled with that approach with this project in many different ways. And so being vulnerable is a whole other aspect of

Brian Smith 39:55

this. Yeah. Well you know, it is really interesting that you said you started this out to be about your rather as a tribute to him, that's, that's really cool, but also shows how we're all inextricably related. So you couldn't do this without including yourself. And now it's, as you said, You're the voice. Now you're the, you're the face of the projects, you've got to come out and do this. And, and it's, and it shows, I love the intergenerational aspect of it. Because as kids, we, I had to I have two children, ones in spirit and one still here. And I was telling people, you should always have at least two children, because you'll realize that you don't create them, that they come in with their own stuff. But on the other hand, we do pick up a lot from our parents. And I think, you know, and I'm 60, now 61. And I still realize how much I picked up from my parents, whether I like it or not. So it's something like this project and kind of help you see where he came from, where you came from, and how you relate.

Zander Masser 40:53

Yeah, and there's a healing nature to that, you know, understanding yourself. Yeah, only way. I think it's, it's healing to understand oneself. And like you said, I think the only way to understand oneself is to understand where you come from. And so when I learned these very difficult, vulnerable stories about my mom and my dad, and what it was like, for her to be his partner and his caregiver, you know, and then how they dealt with that. It allowed me to rethink what my past was, and that carries over to my present and my future. And, you know, it allowed me to build empathy and compassion and just understand how important it is to know someone's story before you judge them, even though we shouldn't be judging anyone. But you can't unless you know what they've been through.

Brian Smith 41:49

Yeah. Well, I truly believe the more that we know about a person we let the less we judge them. And I believe if we knew people perfectly, we wouldn't judge anybody.

Zander Masser 41:59

Yeah, I agree with that.

Brian Smith 42:02

So how was you said you have one child now?

Zander Masser 42:05

Yeah, I have a daughter who's 15 months?

Brian Smith 42:08

15 months? Okay, so you're just getting started on it? Yeah.

Zander Masser 42:11

I'm fresh. Yeah. Although I don't feel very fresh.

Brian Smith 42:15

Well, 15 months? That's, that's, that's rough. So I you know, how do you think this project will impact your your fathering of your child?

Zander Masser 42:25

That's a great question. I think about that a lot. You know, and I write about it a little bit in the book.

I think that, you know, first of all, I want to have a household with open communication. And what that means is that I don't, I don't believe that, you know, parents should or need to share every detail of their lives with their children. But I do think that if there's something in the family dynamic that is impacting or will or could impact everyone, it needs to be talked about in a tailored way. So we don't need to say, like I said, everything all the time. But I think conversations can be tailored to children so that they can understand what's going on in their parents life. So I want to be conscious about that, you know, if I'm stressed or anxious, or if there's something going on, it's impacting my relationship with my child, well, then I need to tell her what's going on. But I also want to encourage her to express herself and share with me and with her mother. And one of the ways that I want her to be able to do that is through creativity. And for her to understand that using creativity is a valid way to express emotions to express feelings. And, you know, like, if I go back to my father, you know, he didn't speak to people about what he was going through. But if you look at his photography, and I say this all the time, there's so much human emotion in his photos, I can sense a man who is feeling a lot, and a man who is introspective and thinks a lot about life and about people and human existence. And, you know, I think that I, I want to encourage my daughter to express creatively, and that there's like, the creative part. And then there's the talking about it. And it kind of goes back to like, what I was saying before about my project about how or creating any projects that opens up the doors to conversation. And so, you know, I want to I want to give her the tools to create whether it's music or photography or art, whatever it is, so you know, creativity and communication need to be consciously thought about and encouraged in the household.

Brian Smith 44:57

Yeah, I think that's awesome. I like He said, it really has to be both. And you know, some people that are very artistic, they pour themselves out through the art. And they're usually deep feelers or deep thinkers. But they don't. But other than their art, they keep it bottled up, and it drives them crazy. You know, we all see examples of artists that just couldn't handle this world, because they just didn't know how to really connect, you know, make that human connection, produce beautiful art, you know, beautiful music, you know, and but just can't, again, make that connection. So I love the fact that you've got that the realization when your daughter's 15 months old, I think it's so important that we reflect. And, you know, I tell people, we can make choices from our parents leave us legacies. And we do tend to go that way if we don't think about it, but we can also make conscious choices. And that's what you're choosing to do.

Zander Masser 45:49

Yeah, absolutely.

Brian Smith 45:52

So tell me, you touched on before, tell me a little bit more about your workshop that you put on?

Zander Masser 45:57

Yeah, so I've been to a few different conferences around US and Canada. I do. So I have a talk like an author talk, or it's kind of like a keynote. And a workshop. They're two different things. But they they kind of go hand in hand. They don't have to. But the workshop is called unburying my grief. And it's a process for creating Memorial Art. And so like I said, Before, I took my creative process, broke it down into 10 steps. And so at every step, there's an actionable item. Sorry, there's a bit of noise. I'll wait till this truck passes. urban living? Yeah. All right. So it's heavy on writing. Although, you know, when someone creates their Memorial Art, it doesn't have to be a written piece. But just the act of writing alone, shows people that they can be creative, because writing is creative. So that's a start. And then at the end of the workshop, when they do all 10 steps, it comes with a workbook, and they've got like a roadmap for the steps that they can follow to create their own art. And so yeah, and it can be delivered in kind of different ways, like a one single session or multiple weeks. And then the talk is a 45 Minute kind of deep dive into the creative and emotional process that went into making my project. And, you know, what it's meant for me, and what the impact is on me and my family, the bleeding disorders community. You know, there's lots of different avenues you can go down, but yeah, it's, it's meant to, you know, talk about all the things we've been talking about the importance of, you know, speaking openly, being vulnerable, sharing our stories, and, you know, the power of, of storytelling and, and not forgetting, you know, whatever it is, whether it's a piece of history, or if it's just an individual life, you know, it's a great injustice to forget somebody's life. So how important it is to remember them.

Brian Smith 48:21

Yeah, well, you know, it's interesting, because I think sometimes people, when they go through grief, they, they, they try to forget, maybe or they say I'm gonna put this aside, but you really can't, you might as well lean into it. And it's gonna, it's gonna come get you at some point, whether it's, I talked to a woman, I think it was 18 years after her son passed before she was really able to turn around and face it and deal with the grief, but it's going to be there. You mentioned your family, what's your family's reaction been to your project? How has it changed the family dynamic, if at all?

Zander Masser 48:55

Um, I mean, you know, they've been incredibly supportive of me. My mom especially shared such amazing, vulnerable content that is in the book. So she was very forthcoming with me in terms of sharing that information, which he hasn't been historically. And so learning her story and the challenges he's has allowed us to repair our relationship a bit, because, you know, after my dad died, a year later, my brother went off to college, and my mom and I were left alone in the home and things were really tense and not good. And, you know, I was directing most of my anger towards her and she was super anxious and projecting it onto me and this project opened up, you know, the lines of communication where we actually spoke about those years, for the first time ever. Yeah, talked about our own sides of the story. And so We've come to, you know, a better place with each other. And she came to. So I was a keynote speaker at the hemophilia Federation of America's event this year, my mom came with me. And it was amazing for her because she met for the first time other spouses and people who lived through the same tragedy that she did, and a lot of people there who wanted to actually hear from her more than for me. And that was so cool for her. And so it kind of brought her into, you know, being more involved in the project. And then for my brother, you know, we've, as I've kind of, like, had some of these revelations about our parents and my dad and the things our family went through. As I share them with him, he kind of has the same revelations by proxy, and we've had some really great deep conversations about, you know, just understanding our family dynamic, and why it was the way it was, and why it is the way it is now. And, you know, we've we've been able to share in that, and he's, you know, he's been involved in the project in terms of just like, you know, I always run things by him and consult with him and ask his opinion. And his voice is very much in the book, his, his voice actually opens the book, with this dream that he had, on the morning that my father died, and just, it's a powerful way to open the book, and he's a really good writer. So, you know, it's been good for our family. Absolutely. But I think I was prepared and ready to be vulnerable publicly. Whereas, you know, I don't think my mom and my brother would have chosen to do that. But they're cool with me doing that. And, you know, sharing my family's story publicly.

Brian Smith 51:59

Yeah, you know, it takes someone to go first to open up and be vulnerable. And kudos to you for being that person to open that door. And my parents are still here. And I and my mother and I had some issues when I was young. And you know, but I'm glad that that she lived long enough. And I lived long enough that we can have conversations about these, you know, some things years later. And, you know, one of the things that I realize is that our parents do the best they can, you know, they they're not perfect people, they they have their baggage, they have issues from their parents and stuff. And, you know, my mother and I shared some of those things. And I'm really glad that we did. So I'm glad you had that opportunity as well.

Zander Masser 52:42

Yeah, it's it's pretty, it's special. And it's important.

Brian Smith 52:47

Yeah, it is. And so for you to put yourself out there and to be vulnerable and to take on this project. And I'm, as people are listening, and what you think of all the different levels of healing that are going on, as you're doing this, you know, your your self, your relationship with your father, your relationship with your brother, with your mother, the way that you're going to interact with your child. And this is all part of your father's legacy. You know, it's and so and you talked earlier, like, well, this isn't about me. But another thing I realized is, most people don't realize, intentionally or not, we're leaving a legacy. We're all leaving a legacy. And most of us having a much bigger impact than we think. And I don't know if you know much about my podcast, but I interviewed a lot of people that had near death experiences. And they talk about having this life review. And they realize the impact that their life has on people. And it's they're not special people. I'm not a special person. But we all have a bigger impact than we think we do. So you're I see your father, as I'm talking. I just see ripples going out and touching so many people.

Zander Masser 53:54

Yeah, well, I appreciate you saying that. And I agree. It's it's very much multi layered. And we all are multi layered every story is. So you're right. Whether we want to or not, we're we're impacting each other. And so we got to, we got to share with each other. Yeah.

Brian Smith 54:13

Well, it's really fun for me to explore those connections and to, again, to just think about, you know, how we're also interrelated and sometimes, like I said, sometimes I'll feel alone. Sometimes we feel like I'm not making that big of an impact on the world. I'm just this or I'm just that. But your your project just again, just illustrates that so well. And so when people get your book and and look at your book, and they think about your father, it's not just about him. It's not just about you. It's about all of us.

Zander Masser 54:43

Yeah, absolutely.

Brian Smith 54:45

Yeah. So where can people find out more about you?

Zander Masser 54:49

Sure. So the website is called Randy Master photo.com. Randy, obviously, it was my father. You can also just Google unvarying my Father which is that title of the book. We can find me on Instagram. Just my full name za n d e r m a s s er who's Andermatt? Yeah, so if you just Google my name Google unburying my father, the website, the Instagram will show up. On the website is where you can buy the book. You can also buy prints. So my dad's photos are for sale. And yeah, I'm around. I exist on the internet and in real life and people if they want to contact me directly can just email me at Xander at Randy Master photo.com.

Brian Smith 55:39

Very cool. Very cool. Xander. It's been a real pleasure meeting you today and sharing this time with you learning more about your father and your project. And, again, I just saw admire the work that you're doing. So thanks for being there for for everybody that's listening.

Zander Masser 55:54

Thanks. It was a really great conversation. So thanks so much for inviting me on.

Brian Smith 55:58

All right, enjoy the rest of your day. Don't forget to like hit that big red subscribe button and click the notify Bell. Thanks for being here.

Transcribed by https://otter.ai

Author and creator

Zander Masser is an occupational therapist, husband, father, musician, and author of the narrative photography book, Unburying My Father. Zander's father, Randy, contracted HIV from using contaminated blood products to treat his bleeding disorder, and died in 2000 from AIDS-related illnesses. Twenty years later, Zander unburied ten thousand slides from Randy's career as a professional photographer, which prompted him to dig deeper into his father's life. What started as a photography project evolved into a transformative exploration of living with, and healing from, grief.